Peter Matthiessen’s work for the CIA ‘sits uneasily within his biography’

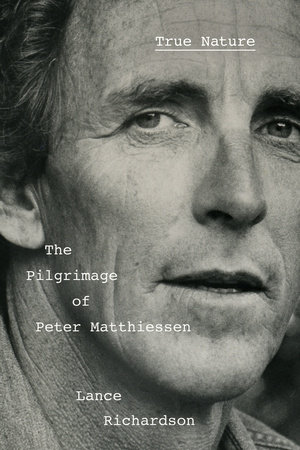

A New Yorker review of True Nature, a new biography of the writer Peter Matthiessen, tells the story of his work as a CIA agent in Paris in the 1950s:

Like many of his contemporaries—James Baldwin, Richard Wright, [William] Styron—Matthiessen was in Paris to channel the legacy of literary modernism and to write innovative fiction. But he was also there on a clandestine mission for the recently formed Central Intelligence Agency, which had recruited him out of Yale and charged him with surveilling Communists and fellow-travellers. (The experience would form the basis for his second novel, “Partisans,” published in 1955.) He founded The Paris Review, with Plimpton and the writer Harold L. (Doc) Humes, in part to give himself a more substantial cover story. As Richardson notes, it’s not clear how much, if any, C.I.A. money went to the magazine. What is clear is that Matthiessen’s socializing with left-leaning French and expatriate artists served the deep state’s agenda.

Matthiessen’s time with the C.I.A. sits uneasily within his biography. He rarely spoke of it, but at least once called it “the one adventure of my life that I regret.” In the years that followed, he tried to make up for his collaboration with the federal government by practicing “advocacy journalism,” much of it written for this magazine. He championed migrant farmworkers, defended traditional Inuit whaling practices, and, at a time when few white Americans took Indigenous rights seriously, supported the American Indian Movement (AIM), a loosely organized, occasionally militant grassroots group that promoted Native traditions and political interests.

This advocacy work culminated with “In the Spirit of Crazy Horse” (1983), a controversial account of the trial of the Native activist Leonard Peltier, who was convicted of murdering two F.B.I. agents, and the F.B.I.’s “war” against aim. Matthiessen, not without reason, portrays the Bureau as paranoid, dishonest, and in league with corporate interests. Soon after the book was published, two libel suits—one from an F.B.I. agent, the other from William Janklow, the South Dakota governor, who was once accused of raping a Lakota girl—took it off the shelves. The book would remain out of print for the duration of an eight-year legal battle that ultimately saw Matthiessen and his publisher, Viking, absolved.