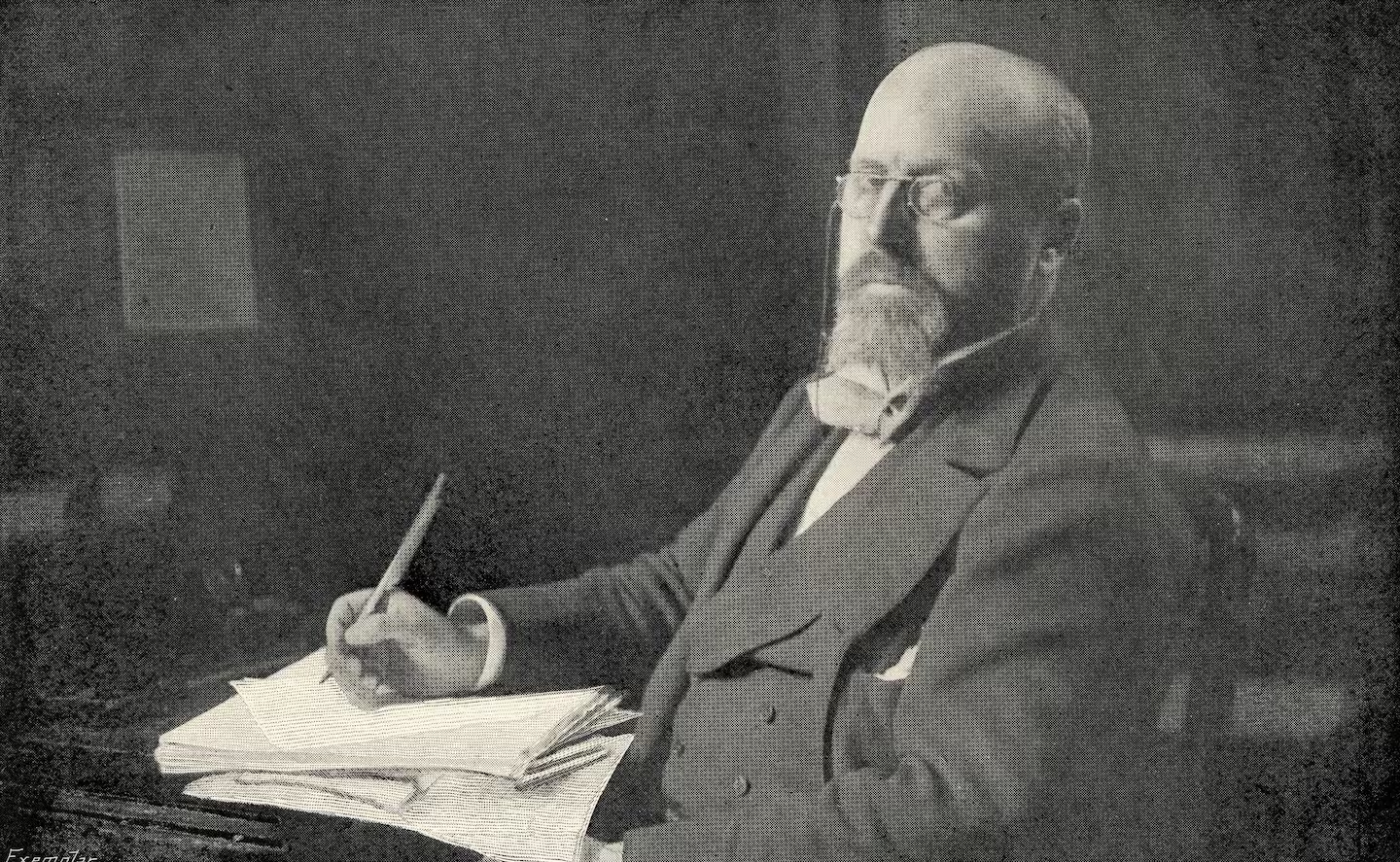

Henry James on how to write a novel

In April, New York Review Books released On Writers and Writing, a collection of 17 essays by 19th- and early 20th-century novelist and critic Henry James. Reviewing it for The Washington Post, Becca Rothfeld summarized James’s rules for novel-writing:

Novels, he argued, “are successful in proportion as they reveal a particular mind, different from others.”

To this tenet he added three others, all of them incongruous in the work of a writer so otherwise dismissive of the abstract and infatuated with the particular. First, he demanded that characters be both “cases” or “types” (favored words) and breathing, bleeding individuals: The novelist “must know man as well as men.” Second, he was emphatic that “character, in any sense in which we can get at it, is action” — that the most elaborate contortions of plotting are worthless if they do not befall believable people. Third, he positioned the novelist as a chronicler of her era: “The effort of the novelist is to find out, to know, or at least to see.” Appropriately, his gravestone in Cambridge, Massachusetts, designates him as an “interpreter of his generation.”

But James’s final principle calls all the others into question. Over and over, he insists on the impossibility of general rules. As he wrote in “The Art of Fiction,” “The only obligation to which in advance we may hold a novel, without incurring the accusation of being arbitrary, is that it be interesting.” His aversion to formulas is closely tied to his chosen genre’s commodiousness. The novel, he proposed, is a boat big enough to “carry anything — with art and force in the stowage; nothing in this case will sink it.” It is the novelist’s job to load his vessel with as much as possible, until it contains a complete picture of its time.